The Stats Guy: What does China’s flawed census mean for Australia?

Key Highlights :

In 1965, official Chinese sources claimed a population of around 750 million people. However, a German news magazine, Der Spiegel, reported that various experts thought the actual population was much lower – some as low as 400 million people. Poor data collection, insufficiently trained staff, and a general lack of interest in accurate data were listed as reasons for the faulty population data.

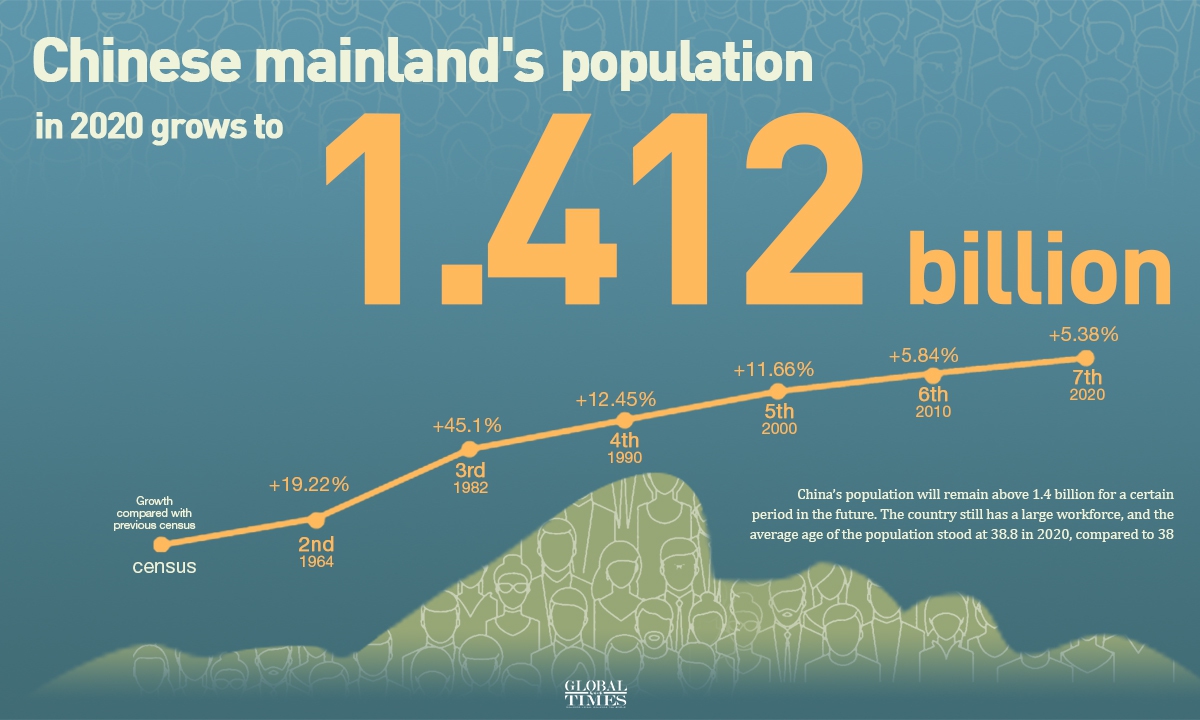

Now, six decades later, China is a vastly different place. It is home to flourishing local industries, globally renowned tech giants, a highly educated local elite, and modern technology. However, history has a way of repeating itself. Research by Yi Fuxian, a demographer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has shown that China has exaggerated its population count for three decades. By comparing the alleged birth figures with subsequent compulsory primary school enrolments, Yi Fuxian suggests that only 1.28 billion instead of 1.41 billion people live in China.

China counting 130 million people that were never born is akin to us noticing that the existence of Perth was but a feverish dream. While a ten per cent discount on your favourite yogurt may not seem like much, a ten per cent miscount in a census is a massive blunder.

The miscount has been attributed to a systemic element. Local governments receive federal funding based on birth registrations. This system has incentivised local officials to round up numbers generously. Some families have even purchased second birth certificates to receive more child-related payments, which has further driven up the low birth rate. As a result, the population miscount is almost exclusively geared towards the bottom end of the age pyramid, while the middle-aged to elderly population is likely to be accurately represented.

Current projections by the UN Population Division (based on inflated numbers) have China’s population at 767 million by 2100, compared to 1.4 billion today. This means that China will shrink even faster, face an even starker aging of the population, and experience less economic growth.

This does not mean that we should forget about China. It will remain a regional giant, with its population continuing to urbanise and grow its middle class, and will continue to purchase what Australia has to sell. China is a net importer of food and energy and is very dependent on a global trade system to feed its people and keep the lights on.

Geopolitical developments suggest a tightening of trade links between Russia and China. A weakened, internationally isolated Russia is good news for China. Russia’s economy has nothing to offer except food and energy, and if the West does not purchase it, China gets a generous discount.

Currently, 40 per cent or US$138 billion of Australia’s exported goods (service trade not included) goes to China. We are overly dependent on a single customer, and must look to diversify trade now. India is an obvious choice; it has decades of population growth and potentially a century of urbanisation left in the tank, and while it is considered a food-secure nation, it needs external energy and mining products.

The moral of the story is that we can be proud of the Australian Census, as we have a very clear understanding of our population. We should also not put all our eggs into one basket, and look for other trading partners. India is a great option, and we should learn from the mistakes of Germany, who were overly reliant on Russia for gas, and paid the price when the war in Ukraine disrupted their supply.

In conclusion, China’s flawed census should be a warning to Australia. We must diversify our trade, and look to other countries such as India, to ensure we are not overly reliant on a single customer.