Unlocking the Mystery of the Ancient Sooty Molecule Found in a Donut-Lensed Galaxy

Key Highlights :

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is set to celebrate its first year of operations in just one month. In the short time since its launch, the telescope has already uncovered a wealth of information about the universe. But as the telescope continues to peer deeper into the distant universe, it has revealed something even more remarkable: the oldest-known instance of a peculiar molecule.

The molecule, known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAS), is sooty and carcinogenic. It is typically involved in the process through which gas and dust condense to form stars. But despite its importance, astronomers still don’t understand all the mechanisms involved.

This is why the recent discovery of PAS within a galaxy that existed just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang is so remarkable. It could challenge our current understanding of when the first star formed.

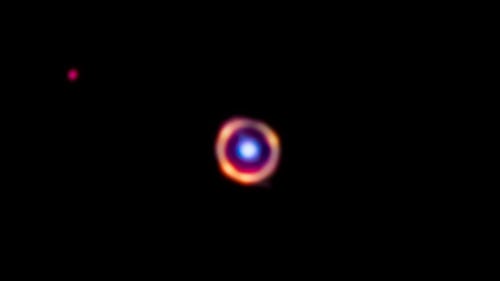

To view the ancient galaxy, astronomers used a phenomenon called an Einstein ring. This occurs when a massive object, such as a galaxy or cluster, bends and magnifies the light of an object much farther away. The result is a high-resolution view of the distant object.

Using the JWST, the team was able to spot the crucial dust within the donut-shaped Einstein ring. This is the furthest back in time that organic molecules have ever been seen in the universe.

The presence of PAS is still a puzzle. Some astronomers think that when the universe was young, it was so much warmer and smaller that massive galaxies may have been able to form stars hundreds of times faster than the Milky Way does today. But they don’t entirely know how it happened.

The discovery of PAS in this ancient galaxy could shift our understanding of when stars formed. It’s likely that PAS are too complex to form alone in the void of space. One theory is that they come from aging stars. When stars die, they start to poof up and get really, really fluffy, and then their outermost layers are barely held on by gravity. So those outer layers just start to float away and cool down as they move further away.

The next course of action is to build context for PAS and gain “some constraints on what is physically going on in these galaxies, what processes are in place, that are leading to this emission.”

None of this would have been possible without the new JWST. Its best work, it seems, is yet to come. With the help of the telescope, astronomers may soon unlock the mystery of the ancient sooty molecule.